So far in this series on the irreparably broken state of Romanian social trust I have taken a synchronic perspective on the erosive effects of interactions between (1) the Gypsies and the ambient Romanian populace; and (2) the Gypsies and the EU.

In chronicling (1) I’ve tried to demonstrate the difficulty of maintaining, or even establishing, a high-trust society as the ethnic majority progressively interpenetrates—genetically and culturally—with its large Gypsy minority, the bearers of an amoral (extended) familistic value system. I have also argued that intermarriage and the Gypsies’ emancipation-though-edyumakashun, combined with their comparatively prodigious birthrate, are probable causes of Romania’s near world-leading dysgenic fertility.

As for (2): free movement within the EU has allowed the Gypsies to accumulate enormous resources from criminal enterprise in Western Europe; and it is in this phenomenon, along with rising intermarriage rates, that I have located the source of growing Gypsy cultural hegemony in Romania.

I have alluded in addition to the disastrous cultural opportunity costs associated with Romania’s EU integration. In the last decade or so the country has lost most of its *cognitive elite* to the West, and with it the possibility of establishing a healthy post-communist counter-model to Gypsy anti-culture (too many hyphens there sorry).

Romania, in short, is Gypsified and dumbed-down—and things ain’t getting better any time soon. Even the fertility rate (much touted, at a near EU-leading but dismal 1.65 per womb-possessor) has been contracting for the last 134 years and, far from recovering recently, has fallen precipitately over the last half-decade or so.

In this penultimate disquisition on the matter at hand I adopt a longer historical view, assisted by testimonies of foreign travellers going back at least two and a half centuries. These accounts show that the Romanians themselves—as a put-upon peasantry historically bereft of a native, Seven-Cs bearing genetic middle class—have long been afflicted by low social trust. In language fashionable about three or four years ago on the new new new new right, this trust-dearth appears to have been a feature and not a bug of Romanian society since at least the 18th century.

But let us partake now of some statistical refreshment!

STATS…BORING

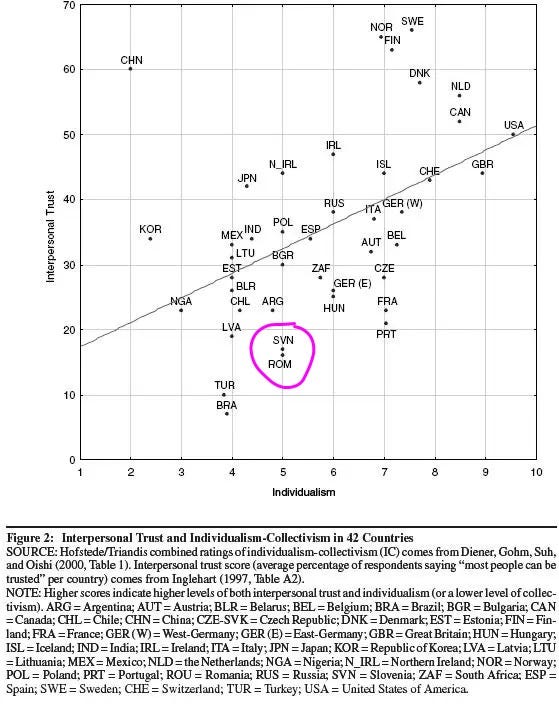

In my initial foray on the present theme I included this chart, which assembles data from two studies conducted around the turn of the millennium:

MY CONTENTION there was that the residual effects of communism cannot adequately explain low social trust in Romania today, and that the country’s reported position on the individualism-collectivism spectrum is also insufficient. Note comparatively high-trust ex-communist Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Estonia—the last four as collectivist as Romania, or even more so—as well as low-trust and individualistic but never-communist France and Portugal. Romania, along with Slovenia, is a European outlier.

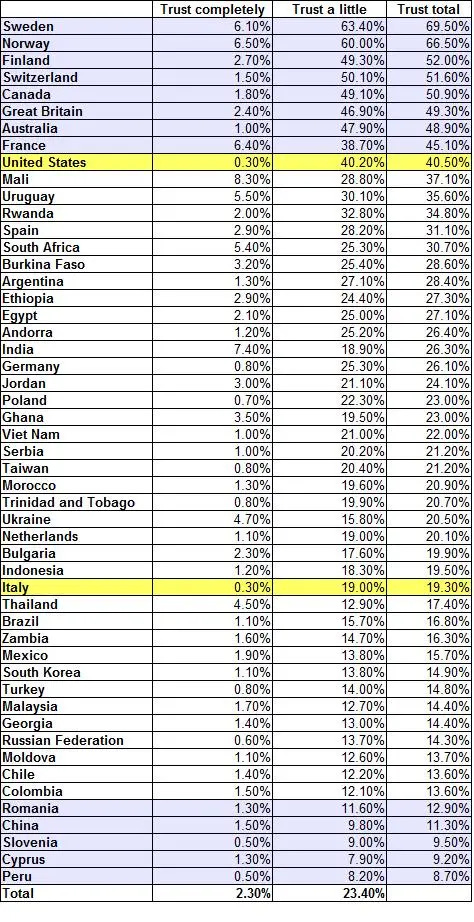

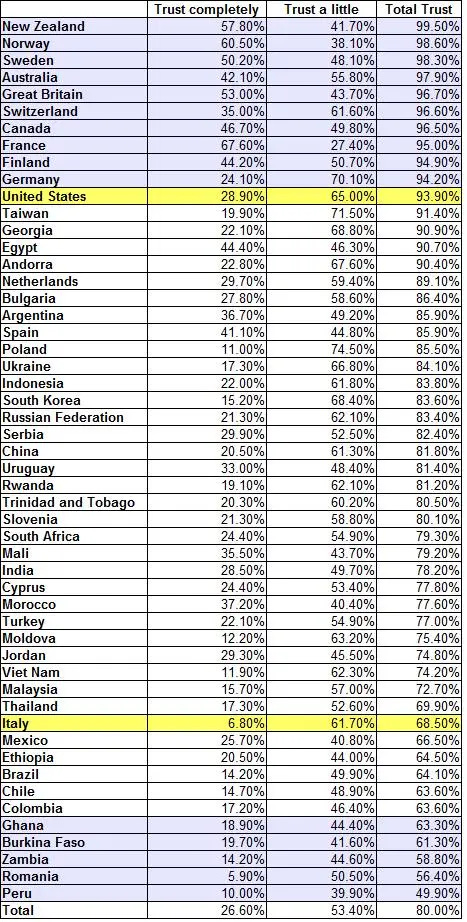

Corroboration comes in the form of the following charts (from HBD Chick), based on results from the slightly later World Values Survey, compiling data from 2004 to 2008 (ignore yellow highlighting).

REGARD: Romania comes out in the bottom five in the dimension of ‘trusting people met for the first time’, and it’s in the bottom three for ‘trust in people known personally’.

OBSERVE: Again, no other ex-communist country—except once more Slovenia—comes close.

HEED: This is in comparison to chronically diverse countries such as Brazil, Nigeria and India.

For a slightly more longitudinal perspective I resort to a section of the World Values Survey which compiles data 1984-2022 (it starts in 1993 for Romania and other ex-communist states). The table below summarises responses to a question on general trust, but the results accord in broad terms with the preceding finer-grained stats.

In this one Romania is within the bottom 25 countries worldwide. In Europe, only Greece, Cyprus and BiH are lower.

Most ex-communist countries suffered from lower social trust in 2022 than they did in 1993, suggesting that the inception of the ‘free market’ has at the very least…not helped. However, while social trust in Romania fell from 16% to 12%, in Slovenia (in 1991 part of a disintegrating Yugoslavia, in 2022 an ‘independent’ nation-state) it rose from 16% to 25%. In 2022 Romania was in addition appreciably worse off than Russia and Poland—and somewhat at a disadvantage relative to (also Gypsy-stricken) Serbia.

NB: Rwanda recorded a higher level of social trust than did Romania.

Elsewhere (check it yourself!) these latest World Values Survey data show that in 2022 Romania was 11th lowest in the world on ‘trusting people met for the first time’ (12%). Among European nations and their predominantly huwhite settler colonies, only Greece, Cyprus and Albania came out lower; Slovenia was a bit higher, at 14%.

On ‘trust in people personally known’ Romania was 15th lowest in the world, at 64%. No Old or New World European-founded nation rated lower as of 2022; Slovenia was measured at 84%.

WTF IS GOING ON?

Of course one might argue that the GQ is wholly responsible for Romania’s miserable showing in successive datasets; the Roma have, after all, roamed on Romanian soil since the Middle Ages. But recall that, according to my confidential SOURCES, Gypsy liberation and concomitantly close intercommunal contact has only commenced since the end of communism—more particularly following Romania’s accession to the EU.

Tenaciously resuming our attempt to place the blame entire on intercommunal disharmony, we might conjecture as to the baleful influence of Romania’s large Hungarian and Tatar minorities, were it not for the fact that each is heavily concentrated in certain parts of the country. Something else, apart from the home-grown diversity ‘advantage’ and the putative post-communist hangover, must be afoot.

One factor contributing to the trust-deficit may be that Romanians at home labour in the midst of a particularly brutal ‘free market’. Wages, for example, are third lowest in the EU, even as wage-earners reckon with exceptionally high inflation (food up 6.2% in 2023, compared to an average rise of 2.9% EU-wide). They also face a de facto flat tax rate of 42 per cent: 10 per cent on income, 22 per cent for social security and 10 per cent for national health contributions. All this means that there is an extremely powerful incentive for people to work as hard as they are able to endure. Many in the lower middle and working classes maintain two or three jobs just to get by.

Low vocational specialisation—men have to do something anything to put food on the table—is among the practical consequences of the harsh and unstable social ecology engendered by Romania’s viciously extractive work-taxation ratio. This lack of specialisation, together with social dumping of cheap Romanian labour in the West, makes it hard to find a genuine and trustworthy plumber or electrician amidst the grasping backyard boys. A second consequence is horrifying traffic. A third, obviously bearing on the second but more in the nature of a spiritual affliction, is the constant rush to catch up with the present, leaving correspondingly little psychological and sentimental room for the past—or even the future.

I think it is partly (not, as I will show, solely) because of his relentlessly present-directed encounter with ecological instability that the median Romanian exhibits a pronounced leaning towards a fast life-history strategy, combining high time-preference and low conscientiousness—all of which are correlated with opportunistic resource accumulation and low trust in others.

The same social ambience and associated trait-suite may partially explain why, generally speaking, a Romanian’s concern for his personal probity is low and his word very rarely his bond. These attributes cannot but militate against the diffusion of interpersonal trust—including, as we have seen, among people mutually well-acquainted.

In this connexion I reiterate that the influence of the Gypsies must not be discounted, even if it is not wholly culpable. As Roma mores become ever more dominant, and the general social ecology ever more harsh and unstable, negative pressure is exerted on European virtues such as truthfulness. Simultaneously, the epigenetic expression of traits associated with a Gypsy-like fast life-history strategy is favoured. These circumstances most emphatically do not conduce to high trust among co-ethnics, especially under present conditions of quickening phenotypic blurring via miscegenation.

How else does Romania’s ferociously low-wage/high-tax regime and resulting ecological instability negatively affect social trust? Certainly sheer desperation, alloyed in unmeasurable proportion with the prevailing zero-sum șmecher/fraier duality, often displaces honesty. For example: attempts are frequent by the aforementioned cowboy plumbers and electricians to overcharge outrageously for services poorly rendered. You rarely know until the job is done, so the safest strategy is to do it yourself. Hardware stores do a massive trade. I thank you Romania for making me into a passable handyman!

One thing is sure: Romania’s currently harsh and unstable ecology must have more than a little to do with the fact that trust in gubmint is statistically on a par with the lowest-tier countries of Africa and South America...

OK that’s enough in the way of statistics about the disgusting present. Let us now try—and fail!—to find consolation in the past.

TRAVELLERS’ ACCOUNTS OF OLDE ROMANIA

As I’ve said *so* many times before, the vast majority of Romanians are at most a couple of generations removed from the peasantry, the usual ‘pipeline’ being: untold centuries in the peasantry -> (urban working class under communism for a generation or two) -> (urban middle class after 1989).

Now think about how many generations have elapsed since your ancestors were peasants. If for instance you descend from Anglosphere New World old stock, with forebears who were pioneers or early NW Euro urban settlers—or even Oirish, Slavs, JOOZ or Dagoes—we’re probably talking at least four or five generations and maybe as many as 10. If you’re an Anglo pureblood New-Worlder, you might have trouble finding a peasant among your ancestors unless you go back to the 13th century or so (not applicable to all you Castizos, quarter-Hindoos and half-Hans out there).

Anyway here's the point: because of their recent emergence from the peasantry, the mass psychology of the Romanians must be different from that of Westerners—and so it is to the peasant past that I perforce turn to account more fully for Romania’s low social trust.

This page, which compiles translated extracts from a 1907 book by the ‘social determinist’ Romanian scholar Dimitrie Drăghicescu, contains much of interest to the present inquiry. Drăghicescu’s own remarks, as well as those of foreign travellers in pre-union Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania, indicate that the Romanian tendency towards present-orientation, low conscientiousness and—let us put it delicately for once—truth-conservation goes back, at minimum, to the 18th century.

As a social determinist, Drăghicescu attributes the expression of these traits not to genes but to what I have called (après Dutton) a ‘harsh and unstable ecology’. Briefly stated, Drăghicescu believes that this ecology was brought about:

as a consequence of the continual depredations of Turkic (Ottoman and allied Tatar) raiders and invaders, beginning in the late Middle Ages;

by rapacious Phanariot (Ottoman Greek) governors and tax farmers, acting on behalf of their Ottoman masters from at least the beginning of the 18th century (so much for the Phanariots as harbingers of modernity huh);

in the 18th and especially the 19th centuries, by the relentless intrusion of market forces and the awakening of the profit motive among the Romanian boyars, who had become heavily Greek in origin and mercantile in orientation1.

Now listen: social determinism is fine as far as it goes. However, being as I am of a reasonably strong hereditarian bent, I have unoriginal reservations of the rightist cookie-cutter type about just how far it goes. How responsive is the phenotype to environmental change? What degree of phenotypic plasticity is required for strong social determinism to be valid? Where do the phenotype and the social milieu—what ya might call the extended phenotype—come from in the first place? Social determinism furthermore confronts the problem of collective agency: are peoples merely acted upon, or do they themselves act?

For his part Dimitrie Drăghicescu opines, with airy authority:

Even in their daily contacts and business, the peasants have an instinctive drive to deceive and cheat each other.

…

They have especially developed a true masterliness in the art of hiding their feelings, ideas and intentions. They are not used to being exact with their statements, assertions or denials. They are afraid of any question and answer as equivocally and deceivingly as possible.

…

Only with great difficulty can one find out the state of their crops. When you ask them, they will instinctively give you false answers. Moreover, if one asks them about the area of land they own one can be certain that the truth will never come out. Usually, no matter what you will ask the Romanian peasant, it is well known that the answer he will give deserves very little trust.

…

By God I do declare that he could be talking about the bloke down the road or the woman around the corner—or even about my mate Cosmin, who in spite of my constant interrogations will never reveal to me THE STATE OF HIS DAMNED CROPS

I’m serious though: the Romanians of to-day are exactly as Drăghicescu described them in 1907. Jarringly for a NW Euro, it’s very difficult to have default confidence in a Romanian’s word, owing to the simple fact that one can never be reasonably sure he’s telling the truth. For the sake of their own survival, the Romanians anciently learned to distrust the Gypsies. The same strategy of default mistrust, it seems, must long have applied in interactions among coethnics—and even in dealings with those whom one knows personally.

WHY WERE (ARE) THEY LIKE THIS?

Drăghicescu again:

Across their entire history, the Romanians concealed their nature; they snatched their life from the sword of invaders and oppressors through deceit and cunning. They had to cheat, conceal, lie and betray in order to save their life.

…

…in order to get at least the minimum of their work results from their oppressors of all kinds: Turks, the fiscal authorities, boyars – the Romanian peasants had to be naturally gifted with a lot of skilfulness and cleverness.

The Boyar Big Man vs Peasant dyad2 and the closely-related șmecher/fraier dichotomy—both of which result in the need to be acknowledged as first (vreau sa fiu primul!) in everything, no matter how trifling—also have deep origins, long pre-dating interpenetration with the Gypsies:

…the peasants didn't have a greater wish than that of being made boyars. Hence, the saying: I – a boyar, you – a boyar. Who will pull on our boots?

A related set of traits—a love of personal freedom and an unshowy contempt for the law, widely regarded as merely a series of obstructions to be circumvented—was also present long ago:

…the Romanians [have] a deep propensity for independence, an unvanquished need for liberty. This deeply felt need for independence and liberty turned into a sort of strong repulsion for any kind of submission. The Romanian began to detest obeying orders, depending on someone else's will or disposition. In our country, all people would have liked to be their own masters and have no master above them.

…which dovetails, now as in the past, with intense Romanian egotism and—once again—the hard sociopsychological opposition of șmecher and fraier:

Everyone's propensity for absolute liberty can be naturally translated in everyone's impulse to master, rule and govern. Jealous of their liberty, everyone could ensure his by stealing that of others.

Mă bă băi frate! It’s uncanny: all the pieces necessary to make up Romania’s current low-trust ‘free market’ ‘society’ were in place among the peasantry as early as 1907!

What of travellers’ accounts, composed 100 years and more before Drăghicescu’s time? They recognise the same pattern of compulsive peasant prevarication.

Thornton (Anglo, 19th? century):

the native Romanians become lazy because they cannot better their fate through work, so they become con artists, tricksters and liars, because the lie is always employed for discovering and wrenching away their few savings.

Comte de Salaberry (French, early 19th century):

“…the injustice and the oppression…force them to be vigilant at being deceived, and thus they end by becoming themselves the deceivers."

Le Cler (French, 19th? century):

“[The Romanians] are cunning; under the pretence of complete indifference, they hide profound simulation."

De Gerando (French, mid-19th century):

“They have cunning, the slave's weapon."

Laurençon (French, early 19th century):

"The serfdom they live in and the extortion that is inflicted on them, made them cunning and deceiving. The mistake belongs to the governments, not to them…the so strangely vicious form of government forces them to resort to tricks that in any country would be considered lies and double-dealing.”

If this was the state of things as early as, say, 1810, how much further did it go back? The correspondence is particularly remarkable between Laurençon’s description and the map in Fig. 1.1.1.4.5.3, quantifying the lack of trust in government among the Romanians of to-day. Could it be that the Romanians were as 19th century travellers describe them for long enough before il diciannovesimo secolo to have become blood-bound bullshit artists and—much worse!—congenital distrustors of GOOD GOVERNANCE OUR DEMOCRACY?! Please consult Cochran & Harpending!

But I don’t want to drone on forever in this UNSCIENTIFIC and NON DATA-DRIVEN manner. Having reviewed Vlach deceitfulness, I now return as shortly as possible to foreign travellers’ accounts in order to adduce, as prefigured far above, evidence of Romanian low conscientiousness and present-orientation…in the past.

A Frenchman, Lefebvre, recounting what he had seen in Moldavia in the 1770s:

"The [Turkish hordes] plunder and oppress the whole country; often destroy entire villages and slaughter the unarmed inhabitants. That is why the Moldavians made a habit of hiding in mountains and forests, taking with them all their valuable belongings…”

…

"The Tartars, 80,000 in number, plundered and laid havoc in all Moldavia for seven days. They took 40,000 men as slaves and spread terror and grief in all corners of the country."

Le Comte de Salaberry again:

“…the Romanian runs and hides; he dwells underground, buries his existence and the few belongings for fear the Turks might spot and strip him. One doesn't spot any house, any dwelling situated so as to see and be seen from afar; except for a few towns, a few scattered hamlets, there are cellars everywhere, underground huts, isolated, hidden by a few pieces of wood and always away from the highway."

Marc Girardin (French, mid-19th century):

"…on a 7-8 hour journey, I saw only five villages and three trees...Elsewhere the highways attract inhabitants, here they drive them away; for on these highways, the Turks' plundering and ravage take place. Therefore, the villages had to hide underground."

Elias Regnault (French, mid-19th century):

"…the highways chase their inhabitants away, one doesn't see any human being on their side. The Turks came on them; people fled in terror; both houses and villages were moved and settled far away, in the hollow of some dale, on the slopes of some mountain.

When the plunderers pursued their prey, reaching some hidden village, the inhabitants that survived the invasion hurried to gather their few belongings and went to rebuild their huts in an even more isolated place.

Because of these permanent migrations, the villagers always changed their location; the barbarian invasions established a mobile geography on the country's area."

The picture presented in these travelogues, then, is of a people beset by horse-borne marauders, exhausting labour exactions and ruinous tithes—and thus cursed by impermanence and the inability to plan ahead. I am again astonished by obvious parallels with the present3. Indeed, Romania’s ecology has been more or less uninterruptedly harsh and unstable, a field for constant incursion and despoliation, since prehistory–and this to a much greater degree and for much longer than was the case in northwestern Europe. In my next poast I will delineate a number of contemporary manifestations of the Romanians’ present-orientated psychology.

Drăghicescu, quoting extensively from the Romanian polymath Constantin Radulescu-Motru, has the following to say about the effects of sustained pre-20th century ecological instability on the Romanian character:

…everything is done in our country quickly, in a hurry. "The Romanian…is in a rush at work, just like at war. He works wonders with the haste. The peasant accomplishes, in a few hours of group work, a job that he couldn't have performed even in a week."

“A waiting moment exasperates us and exhausts our patience, but we can handle just fine a few months' indifference. Our field worker gets tired as soon as he is constrained to a too rigorous discipline. He likes…extremely intense strain, but not continuous”…

"A whole year the Romanian idles, and in the last days of the year he works double tide…"

"There is nowhere else more fret, more turmoil, and less disciplined work as with our people… In us, there lives the soul of our primitive shepherd and farmer ancestors, a soul that puts itself about a few months a year and hibernates the rest of the time. We are capable of any virtue as long as it doesn't entail too long a persistence."

So now at last I find that I have said my piece. The Romanians have long historical form as truth-disdaining, low conscientiousness, excitable and explosively obstreperous high-time preferrers. The expression of these characteristics has probably been successively dilated and updated by communism, inter-assimilation with the Gypsies and the harsh & unstable ecology created by the modern kleptocratic state. But the longer historical view shows that the characteristics themselves were not begotten by Romanian-style modernity.

I apologise for the lack of attempts at humour in this one, by the way. In the FINAL (YES maybe FINAL) entry on Romania I will ever make—which will probably not be at all funny either—I get around to something resembling ethology, because it’s right there in the name of muh stack.

By the dawn of the 17th century many of the old TOCHARIAN-CUMANO-VLACH aristocratic lineages had been extinguished in centuries of warfare—even the venerated Mihai Viteazul himself was probably Greek on both sides—and their customary warrior prerogatives were at last utterly destroyed in the mid-18th century by the perfidious machinations of greasy Phanariot taxation.

As I’ve said before, the Boyar Big Man, an archetype set deep in the collective consciousness, has with the increase of late in Gypsy power come to be represented by the bulibașă.

Turkic rapine currently excluded—though this may soon be remedied, judging by the alarmingly large number of leering Anatolian immigrants milling about these days

All the facts are falling into place. This is a masterful presentation. It's looking more and more as if the foundation of social trust is...

“A waiting moment exasperates us and exhausts our patience, but we can handle just fine a few months' indifference. Our field worker gets tired as soon as he is constrained to a too rigorous discipline. He likes…extremely intense strain, but not continuous”…

"A whole year the Romanian idles, and in the last days of the year he works double tide…"

"There is nowhere else more fret, more turmoil, and less disciplined work as with our people… In us, there lives the soul of our primitive shepherd and farmer ancestors, a soul that puts itself about a few months a year and hibernates the rest of the time. We are capable of any virtue as long as it doesn't entail too long a persistence."

The above describes me perfectly.